The Keep on the Borderlands is Full of Lies

“Welcome to the land of imagination.” That is how The Keep on the Borderlands chooses to introduce itself, as if Willy Wonka is inviting you into a confectionary sweatshop. B2: The Keep on the Borderlands (hereinafter, simply “Borderlands”) is probably the most-played adventure of all time by virtue of being included in the Basic Set of D&D at the dawn of the hobby. Since then it has been emulated by adventure writers the world over, in ways both intentional and unintentional. In Gus L’s review of Borderlands for D&D’s 40 anniversary, he summed up the high esteem in which this adventure is generally regarded: “It’s iconic and widely adored, the Ur module.” This sums it up. But there is a spectre haunting the Borderlands. The module isn’t what it seems. I will first discuss how the module frames itself and the player-characters before revealing the sinister secrets hidden within. No prior knowledge of Borderlands is required to ride this ride, but it will contain spoilers, if you are worried about spoiling a 42-year old adventure.

Author’s Note: I am not trying to police anyone’s fun. I think running Borderlands entirely straight could be a lot of fun. However, I want to present a reinterpretation based on the text of the adventure. I present a world that is less black-vs-white and more gray-vs-gray. This tends to open up more choices for players to make. And more choices lead to better games.

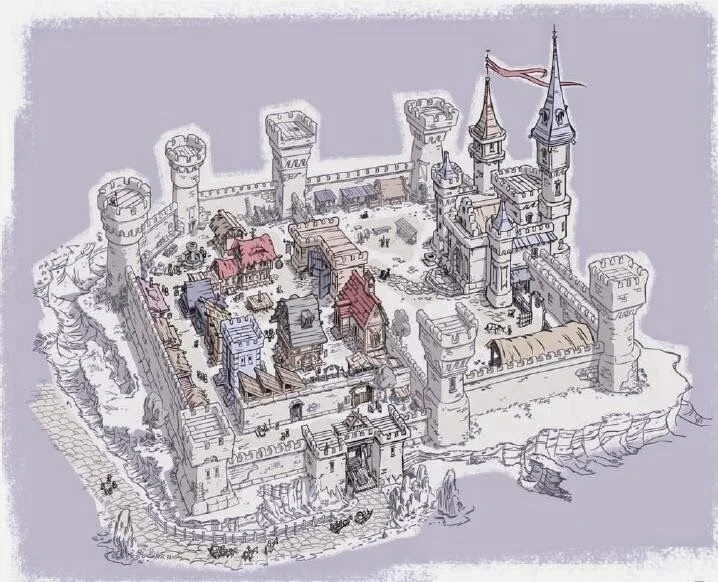

You Play the Good Guys

“There are always certain exceptional and brave members of humanity, as well as similar individuals among its allies - dwarves, elves, and halflings - who rise above the common level and join battle to stave off the darkness which would otherwise overwhelm the land.” Perhaps you’ve heard fantasy settings called “points of light,” a phrase predominately used in the Fourth Edition of Dungeons & Dragons to describe its default setting. But BX D&D was there first! Borderlands is not just a points of light setting, it is a point of light. The eponymous Keep exists amid myriad dangerous and chaotic forces. The Keep is “one of civilization’s strongholds between good lands and bad.” The player characters arrive with “heart[s] that [cry] out for adventure,” so they have come to the Borderlands to make “forays against the wicked monsters who lurk in the wilds.” To satisfy their crying hearts, they are sent to the nearby Caves of Chaos (hereinafter, the “Caves”), “where fell creatures lie in wait.” 65% of the rumor table for the Keep is all about the Caves, and many of the other entries are tangentially about the Caves. It is the talk of the town. And once there, it is primarily a slug fest. There is little information given about the motivations of the Caves’ denizens beyond wanton destruction, so player-characters must clear the caves with bloodshed. No treaties are to be negotiated. This is a tale as old as time. The heroes are exceptional people, defending the good from all the evil that means it harm.

Unreliable Narrator

The tone of Borderland’s Background section left me a bit incredulous. It paints a picture of a contest Good versus Evil. The Keep and its inhabitants are Good, the monsters in the Caves are Evil. The player characters must “remain faithful and ready to fight chaos wherever it threatens to infect the Realm.” The player-characters must be the fittest, in the social Darwinist sense: “adventurers meet the forces of Chaos in a testing ground, where only the fittest will return to relate the tale.” The evil denizens of the Caves “press upon [the Realm’s] borders, seeking to enslave its populace, rape its riches, and steal its treasures.” Frankly, it sounds like thin blue line propaganda—the adventurers are all that stands between the Realms of law and good and the forces of Chaos which threaten to overwhelm civilization. But maybe the Keep really is so good and virtuous! Let’s see…

If any member of a party should be caught in a criminal act, the alarm will be sounded instantly. Citizens will try to prevent the escape of any lawbreakers (without sacrificing their lives) until the guard arrives in 1-2 turns. If met with resistance, the guard will not hesitate to use force, even killing if they must. Those offenders taken prisoner [and] locked in the dungeons under the Keep and punished for their crimes.

The above is from the first DM note about the Keep, presumably the most important aspect for the DM to keep in mind when the player-characters are in town. From just this snippet, it sounds like the Keep is a bit more complex than just a stronghold of good. It is a police state. Guards are so plentiful and active that they arrive just minutes (1-2 turns) after a crime is committed. This is quite extreme, especially for the quasi-medieval assumed setting. As stated in this classic post from Against the Wicked City: “Compared to modern states, most pre-modern polities are ramshackle as fuck. Remind your players early and often that just because they have 'a government' doesn't mean they have anything resembling a modern bureaucracy, with a police force and a civil service and so on.” In the Keep, not only is there an active police force, the citizens are so dedicated (perhaps brainwashed, but that is unclear) to the cause of law and order that they will go to any length short of risking their own life to apprehend criminals. And when the offenders are captured? They are “taken prisoner will be locked in the dungeons under the Keep and punished for their crimes.” The Keep has a modern police force but no modern judiciary, no trials, no rights for the accused. Habeas Corpus is a spell that simply has not been invented yet.

The narrator’s pro-Keep bias persists beyond their description of the Keep. For instance, between the Keep and the Caves, there is a (sparsely keyed) wilderness. In the wilderness, one of the encounters is a “Raider Camp” containing a “party of a dozen chaotic fighters.” They have wine and venison but, more sinisterly, are described as “close enough to be able to spy on the Keep, far enough away so as to be unlikely to be discovered by patrols.” However, to me, this reads like a description of Robin Hood and his Merry Men if written by the Sheriff of Nottingham. It is a band of outlaws hiding out from authorities in the forest. The leader even fights with a bow and arrows! They are called “raiders,” but whom are they raiding? It seems like they are antagonistic to the Keep and its agents, so that is my guess. The group is certainly chaotic (just as the Keep is lawful), but the narrator’s bias shows in their positive portrayal of the lawful Keep and negative portrayal of the chaotic outlaws. From a different point of view, the raiders are chaotic but noble in their rebellion against an oppressive state. How often is the Sheriff of Nottingham portrayed as the hero of the story just because he is lawful?

Pushing the Borders

“The Realm of mankind is narrow and constricted. Always the forces of Chaos press upon its borders.” This is the first line in the Background section (the first line of the narrator—before that it is simply Gygax as Gygax giving GMing advice). But is it true? Returning briefly to 4e D&D’s Points of Light setting, the “Realm of mankind” is certainly in decline. People live in the wake of fallen empires, and ruins dot the landscape. This is a world in which chaos is pressing on the borders of lawful societies. But while the Keep exists on the borderlands of this Realm of mankind, it appears that the border is expanding, not contracting. If it were contracting, we might expect abandoned keeps or other ruins of mankind beyond the Keep. Instead, there is nothing of the sort (although, again, the wilderness is lightly keyed). Instead, the Keep seems to be built to mark and defend the borders—it is an expansionary project, an imperialist project. Does the enthusiasm to clear the Caves of their monstrous inhabitants stem from a desire to protect the Keep and its citizens, or from a desire to expand further?

The very structure of the adventure is evidence that, even if the Realm of mankind is narrow and constricted now, it is attempting to expand. If the forces of Chaos were truly hellbent on the destruction of the Keep and all it represents, perhaps there would be evidence of a recent assault on the Keep when the player-characters arrive, an assault that the Keep was barely able to fend off. The Castellan implores the player-characters to lend a hand to protect the Keep from a vicious onslaught. The combined forces of Chaos, a rare alliance between goblins, gnolls and orcs, rally an even larger invasion force, and the player-characters must rally the Keep and beat back the advance of Chaos. After they save the Keep from certain destruction, the player-characters would then sally forth to deal a final blow to the remaining agents of Chaos, who fled the battle of the Keep with their tails between their legs. This is not how the adventure is structured. It is the player-characters, as agents of the Keep, that make the first move—invading the Caves of Chaos. And it doesn’t appear the fractious tribes pose any threat to the Keep. They aren’t making any attempts to join forces. Even the orcs have a tenuous relationship with…the other orcs. And you won’t find any siege weapons under construction in the Caves of Chaos. Instead, you mostly find tribes of these humanoids, simply residing in their homes. The module takes great pains to illustrate the family structures of these groups. Even the number of young is listed. They do mostly attack the player-characters on sight, but is that so unreasonable in the face of a home invasion?

Choose Your Own Adventure

I apologize to anyone whose youthful memories I have sullied with this interpretation of a beloved adventure module. But this interpretation makes Borderlands a richer adventure. The player-characters can still set out to delve caves and kill monsters, but now there is a possibility of intrigue as the more sinister truth of the Keep shines through its propaganda. The players are not de facto agents of the Keep. They may still side with the Keep, but they may also join the band of Raiders and wage covert rebellion against the corruption in the Keep. Or they might unite the tribes in the Caves, lead them to raid the Keep and push back on imperialist encroachment. No choice is necessarily the right choice, and that is a virtue. The opportunity to put the Keep to the sword or join a band of raiders also fixes one of the flaws in the module. As Gus L says in the aforementioned review, “loving detail is heaped on the Keep itself to almost no purpose.” It fills 6 pages of a 28-page module, detailing all the riches of the Keep. These details aren’t particularly useful if there is no adventure to be had in town. But if the player-characters plan a heist or a full-scale assault of the Keep, these details become a real aid for a referee trying to roll with the punches. The Keep, the Caves and the Borderlands are so much more vibrant when they are depicted in shades of gray, not black and white.