A LEGO Jam Retrospective: Trouble in Paradisa

When I was a child, I played as a child

When I was a wee lad, I was a fiend for the little, stubbed bricks of plastic that interlocked with each other, or as they are more commonly known, Legos. In 1999, when Lego first began manufacturing sets based on Star Wars, a popular science fiction motion picture series of the time, I was 5 years old and the ideal mark for the new line (so obsessed was I with the impending release of The Phantom Menace that my pre-literate self produced a “machine”, a box full of loose wires from broken toys and drawings of Darth Maul and other characters from the promotional onslaught, in hopes that said machine would allow me to watch the movie early). My first set, as I recall, was 7110 (Luke’s Landspeeder), but of the 1999 Star Wars sets, I had 7101 (Lightsaber Duel), 7130 (Snowspeeder), and 7140 (X-wing Fighter, by far my favorite).

I, of course, didn’t limit myself to one intellectual property. Such would be pure folly on the level of only ever playing one tabletop roleplaying game and claiming that it can cover any type of game! Surely, no one would do such a thing. No, I was equally enamored with the Lego Ninja subtheme of Lego Castle and the Lego Adventurers set (a clear “homage” to Indiana Jones). Not to mention my uncle, who grew up in the 1980s heyday of both D&D and classic Lego Castles & Space themes), had left many of his Legos behind at my grandparents’ house for my perusal.

When Akira Toriyama died earlier this year, it spurred me to examine what I found so enchanting within some of his best work. One aspect I identified in that piece was how he didn’t hew to the adult (derogatory) drive toward taxonomical separation: spaceships and dinosaurs existed side-by-side. True to form, as a child I did not see Star Wars sets, Castle sets, and City sets as all existing in separate worlds. They were all part of a weird kitchen-sink Legoworld type setting. That is how the overalls-clad pizza delivery boy from 10036 (Pizza To Go) became a lightsaber-wielding villain that also delivered pizza. There was simply no contradiction to delivering pizza and delivering fatal blows with a laser sword. (I’m not alone here—right before publishing this, my colleague, Ian of the Benign Brown Beast blog, posted his own bootleg version of Star Wars from his childhood as his submission to the Lego Jam).

Paradisa Lost

I do not know how I came upon Paradisa sets. This sub-theme of City, which was marketed toward girls, focused primarily on beach scenes and horseback riding and I came into possession of a few of the sets as a youngin. Namely, 6402 (Sidewalk Cafe), 6411 (Sand Dollar Cafe), and 6416 (Poolside Paradise). Somewhere between moving houses, we must have lost the baseplate to 6416, but I remember recreating it using the identical (except color) base plate from 5978 (Sphinx Secret Surprise), expanding it and even submitting our larger beach scene to the Lego magazine of the day (which regularly featured fan creations).

When my colleague, Anne of the DIY & Dragons blog, issued her call to action for the Summer LEGO RPG Setting Jam, Paradisa quickly came to mind. This was because themes like Castle, Space and Pirate all felt too immediately gameable. Who is to say that the Space Lego Theme isn’t already a Mothership setting? It sure feels like it might be. I wanted something that challenged me to make something that didn’t feel like a typical TTRPG into one.

And I immediately cheated. My submission for the jam, Trouble in Paradisa, adds a twist not present in the sets: there has been a murder! Murder mysteries are a tried-and-true formula for tabletop gaming. Just look at the success of something like Brindlewood Bay or the musing of my own old post on the subject. But there is no indication of murder in the sets themselves. Nary a single gun in the sets (although the absence of violence is shared with the classic Space sets). If I were to approach Paradisa with perfect fealty, something more akin to Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast (I eagerly await my copy landing on my doorstep, any moment now, as I write this) would be more appropriate–not focused on anything to solve so much as on characters, their relationships with each other and their relationship with the place they are in Paradisa. In Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast, it is always September 15. In Paradisa, it is always the first day of summer break, your whole vacation stretching out as far as the ocean horizon.

However, my take on the Paradisa theme is more in keeping with how I played with them as a child. I had plenty of lego firearms and swords and lightsabers, and my Lego citizens were always in the midst of dealing violence to each other or threatening to do so. Murderhobos long before I ever laid eyes on a d20. The same was true of other purportedly nonviolent themes like Space. You can bet that I gave the monkey from the Paradisa 4 lightsabers to hold at once–why else have 4 hands?! So I didn’t feel I was violating the sacred peace of Paradisa by introducing one extra piece: a handgun, which has gone missing after a mysterious death.

Now my Paradisa was more akin to a season of White Lotus than to the peaceful vacation promised by the promotional text for Paradisa in the pages of Lego magazines (which promotional text I reused on the cover of the pamphlet adventure, with only minor modifications). But what was my process?

This Side of Paradisa (the inside)

The first step after you have your idea and the possibilities are endless and your imagination is running absolutely hogwild, is to add some constraints. I have always found that some constraints help me focus and promote within me a level of additional creativity. It is why I like to write in “mock-layout”, which bears only a passing resemblance to the final layout of my work. It is to grease the wheels on my train of thought, not merely to assist my gracious layout artist (my wife [read this in the voice, you know the one]). Luckily, Anne already provided one constraint in her challenge: “I encourage you to think small, to be expressive and concise, and to write a setting that will fit on 1-2 pages of 8½ × 11 paper when printed out.” (However, Anne has clarified that this is only a suggestion and not an ironclad rule–in fact, one of the best submissions so far from my colleague Josh of the Rise Up Comus blog could probably fill a full-sized zine.) I took up Anne’s limitation and adding one of my own: I would limit myself to four sets from the theme.

My centerpiece was the aforementioned Poolside Paradise. Not only was it the Paradisa set I remembered best from childhood, but it also perfectly reflected my vision of a White Lotus-esque setting, a luxury hotel in a beautiful resort. However, such a resort would need more than just a hotel, so I enlisted 6410 (Cabana Beach) as the resort’s private beachfront, 6411 (Sand Dollar Cafe) as the hotel’s associated restaurant (likely not owned by the same private equity firm that owns the Poolside Paradise, but Lego doesn’t yet make a real estate attorney set to hash out the complex lease structure between the hotel and restaurant), and 6414 (Dolphin Point), which is also beach-themed but by virtue of being an island, is far enough from the rest of the resort to allow a bit more intrigue. Also, it makes the characters need to use boats to fully explore the full set of locations detailed in the adventure. Two other sets are implied to exist in the text of the adventure: 6418 (Country Club) and 6419 (Rolling Acres Ranch). This is not only as part of the conflict (Maria owns Rolling Acres Ranch and is trying to get Bree, the city planner, to approve the addition of the Country Club) but also to imply that all of the other Paradisa sets, and perhaps all of the rest of the City sets, exist within this world. Referees don’t need the permission of the adventure to expand it in any way they see fit, but with such a small space, I at least wanted to gesture in a direction they could expand it if they choose.

After I had my sets picked up, I needed my dramatis personae. I simply looked at the four sets and cataloged each minifigure that was included. Where a sufficiently identical looking minifigure was included in more than one set, I decided that was simply the same person (although, as my wife noted when reading the incredibly soap-opera-esque connections between the characters, all that is missing is an identical twin subplot). I then picked one character, at random, to be the murderer, picked a few that seemed to be working at the locations (in a theme all about leisure, it seems it was impossible for the Lego designers to obliviate any hints of work, the enemy of leisure), and decided that all the remaining characters were guests at the resort when the murder went down.

I added flesh to my plastic Lego characters using a 14-pointed star. This is similar to the “faction pentagram” method I described in the portion of Part Two of my Hexcrawl Checklist devoted to adding competing factions to an area. I placed the murder victim, the staff (including the monkey) and resort guests in a 14-pointed star formation and drew a circle around the point of the star. Now each character had 4 connections, 2 which were negative (the star) and 2 which were positive (the circle). It was then my job to start to explain why there were these connections. The tool told me only if two characters liked or disliked each other, but I had to supply the reasons, the history. As I completed the prompts, characters started emerging from the glossy yellow faces splayed before me. Tanner is an absolute jerk and truthfully a bit of a loser. Lorenzo is a work-obsessed control freak. Summer is lowkey abusive. Dario is a bit of a playboy with a jealous streak.

Once I had these connections, they led me to my conclusions about who was involved in the murder and why. After the 14-pointed star method, this felt like riding downhill–it was clear who might want Joan dead and why, I merely had to pen down how and when. Of course, there were others who make sense as the murderer, but I didn’t consciously place these characters as red herrings; they merely emerged as such. I won’t say who is who, but there are at least four characters who are plausible as the murderer. It is up to the characters who suss out which one did it.

Once I had the murder down, I needed to describe the impact those events had on the locations. Where is the gun, and who knows (or doesn’t know) where it is? Did blood get on anything? Where was the victim last seen, with whom, and what was she doing? Just like the character connections made writing the murder a simple exercise, once the murder was penned, it was relatively simple to supply these answers.

Now that the text was final, I handed it to my expert layout artist. K.T. Nguyen is a veteran layout artist, and you likely know her work from the award-winning Barkeep on the Borderlands. She took quickly to this assignment because the Paradisa sets, with their vibrant hues, were already so vibey. She merely followed those vibes and built upon them. The first spread, with the sets, looks like an advertisement that a 1990s Lego executive would have likely killed for (as long as they were likely to get away with it). An especially nice touch was the Trouble in Paradisa logo, a subtle reworking of the logo for the original theme.

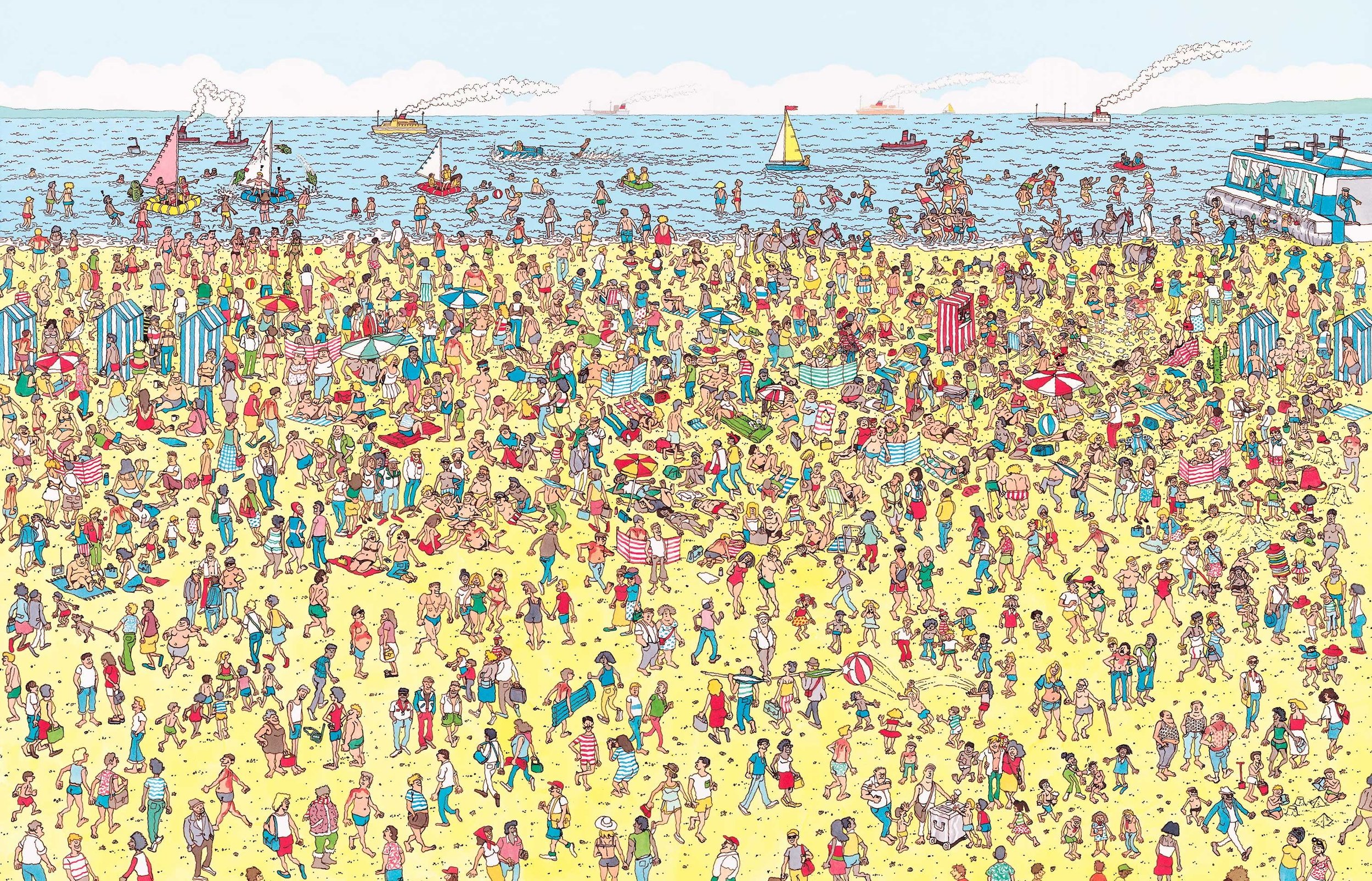

The use of the Legos themselves are essential for making Trouble in Paradisa playable using such little space. A third of the space is devoted to the space themselves and, importantly, they are on the outside of the pamphlet. The idea here is that you could use the pamphlet as a GM screen–everything on the exterior is helpful to show the players. They can look at the sets and decide where to investigate next or which characters they would like to question. This is very much in keeping in the “Picture Book Gameplay” theory posited by my colleague, Dwiz of the A Knight at the Opera blog. The outside page might as well be an in-universe travel brochure for the resort.

This image is gameable.

The inside panels are for the referee's eyes only, as it contains all the sordid secrets of the murder. There are two graphical nuances to the interior: the first is similar to the inclusion of the sets on the exterior: K.T. used the headshots for each character alongside their description. If the players tell the referee that they want to interrogate the guy in a white shirt, blue hat and no mustache, the referee can look at the images and realize “Oh, that’s Connor.” (Although Dario and Tanner are only differentiated by their different shades of hair, but otherwise dressed identically–I hope that causes some groups to think perhaps some eye-witness accounts involved mistaken identity, or allows for other shenanigans.)

The other graphical trick is simple. The backdrop for each of the sections on the interior are shaped like file folders. This is just subtle messaging that the role of the players is as investigators. Of course, the adventure can’t prescribe its use–you could easily take this and roleplay as one of the pre-established characters. But the last paragraph of the intro text is the only other indication that the intended use is that the players are investigating a crime. With such little space, we had to think of ways to communicate this fact efficiently. I think the file folders do the trick.

The adventure is system-neutral (and, indeed, is system-agnostic) not only because adding vestiges of system would only interfere with our limited space, but because mysteries as a TTRPG genre don’t have the same baggage that fantasy does. When writing anything in fantasy, people are conditioned to want to know the vital statistics of all potential enemies in case they come to blows with it. This is deeply embedded in the genre from its D&D roots. I have written before on system-neutral solutions to this issue, but there was no need to employ them here as there was for something more fantasy-forward like Barkeep on the Borderlands. In Trouble in Paradisa, the players might come to blows with a character, but it isn’t on the table as much as it is when you play characters with swords and shields and wands of fireball. There is, of course, the implication of violence since I placed a gun into the scene. But I would simply rule that, if the players get shot at with the gun, they die, and if they shoot at someone else with the gun, they die. Make the decision to pull the trigger really matter, and let the dice fall where they may, without the need to roll any dice.

Housekeeping

Now it is time for you to participate in the Lego Jam! The scope is entirely up to you–take your favorite theme from your childhood or just one particularly memorable set and build something gameable around it. For me, it was an enjoyable exercise, but I also enjoy reading all the other entries people have put out thus far.

That isn’t your only jam assignment for the summer. You, yes you, can join the Mount Rushmore that is Barkeep on the Borderlands Contributors (Luka Rejec, Zedeck Siew, Ben L., Gus L., and the list goes on) by making your own pub and submitting it to the Barkeep Jam, which is running from now until August 14. Get to jammin.

Speaking of cool stuff people are making for Barkeep, check out these coaster printouts that my colleague over at the Technical Grimoire made. Coasters on one side, and drink menus for the other. Perfect handouts to your players as they come across a new pub in the adventure. And on the topic of cool riffs on my work I’ve seen in the wild, Carpengizmat has a neat (and really well produced) video discussing my recent cooking rules.