How to NOT Run You Got a Job on the Garbage Barge

As a general rule, I try to cede to the players as much authority as I can when I run games. One way this tendency manifests itself is, after assembling a group of players, I poll them (using ranked choice voting—sorry, NYC) on what adventure and/or system they’d like to play. I offer a number of alternatives, each of which I would be excited to run. The most recent time I did this, a winner emerged in the second round of voting: You Got A Job on the Garbage Barge by Amanda Lee Franck.

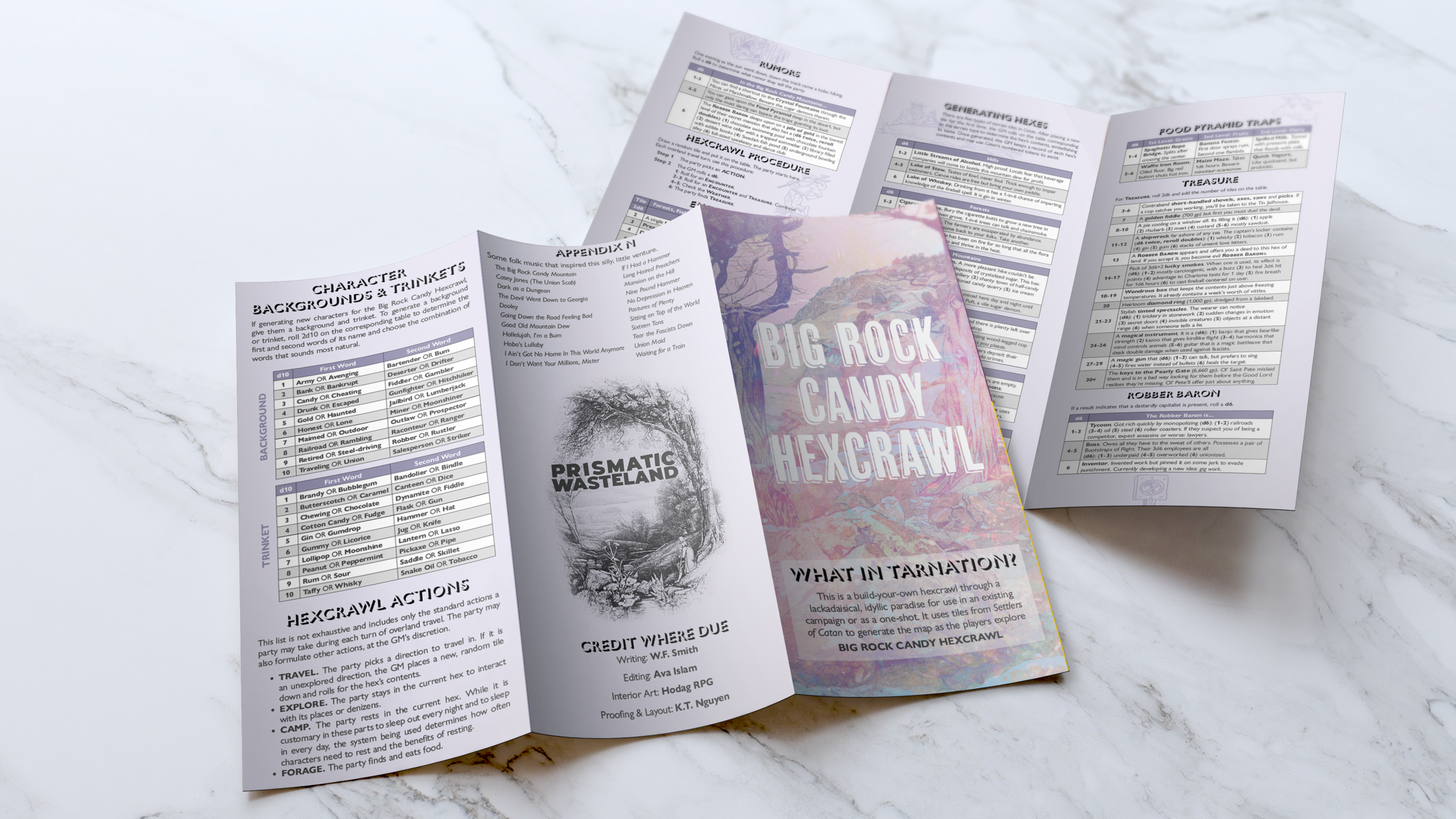

IGNORE THE TYPO ABOVE. Here is the image I used in pitching the game ahead of voting. I will not share the pitches that were not selected, out of respect to the losers (my own upcoming game, Big Rock Candy Hexcrawl, among them. RIP).

You Got a Job on the Garbage Barge (as used herein, “GarBarge”) was funded in 2020 as part of ZineQuest 2. In addition to its primary author, Amanda Lee Franck, it had several OSR luminaries as guest writers including Aaron King, Dungeons and Possums, Sasha Sienna & Jonathan Sims, Scrap Princess, and Zedeck Siew. GarBarge is both adventure and setting, all taking place atop and within the eponymous garbage barge. However, this blogpost is not a review of GarBarge (if you are in search of that, check out this review from Mazirian’s Garden). It is a record of my hubris, my folly. It is a play report but it is also a warning to those who might repeat my mistakes.

If you want to run an adventure, you should start with that adventure. To the extent I have advice on running GarBarge, that’s it. Begin the adventure on the barge, the player characters already gainfully employed thereon. No need for baroque foolishness. Because I am nothing if not a baroque fool, I had other plans. I thought it would be fun to begin with Canal of Horrors, an Electric Bastionland adventure by Chis McDowall himself that was included in the Dissident Whispers anthology (if you haven’t already picked it up, I highly recommend that you do so posthaste). The premise for the Canal of Horrors is that a luxury yacht lies unclaimed at the docks, but the party must get there while being pursued by Rich, Future Bastard Versions of Themselves (there are other options, but this was too good to not use). My plan was for the party to begin as intended in the Canal of Horrors, but instead of seeking a luxury yacht at the docks, they seek a lucrative career upon the garbage barge that just sailed into town. In theory, these adventurers connect without much effort. And the classic McDowallian hook of being deeply in debt provided a good reason for players to seek the treasure that no doubt rotted amongst all the unwanted things on the barge. But there was a key element for which this plan failed to account: the players.

Perhaps investing the players in the world outside of boats full of trash was my first mistake. Drawing more from story-game traditions, I run character creation as a collaborative mini-game where the players get to collectively shape the world by building their characters. As a byproduct, the players get invested in the aspects of the world they help create, I learn a bit about the type of game that they are interested in running, and we are all on the same page about the “lore” of the world. When they decide that humans are a formerly extinct species that were brought back by the spacefaring elves that rule Bastion, they now know just as much about that fact as I, the referee, know. The characters began their world building efforts from the failed careers they rolled from Electric Bastionland (we were otherwise using rules from Prismatic Wasteland. I can never resist an opportunity to play test my opus-in-progress). They decided that their collective debt was conglomerated medical debt, so rather than the trite starting at a tavern or other drinking establishment, they began in a Bastionland hospital (though not quite Bastionland, as mentioned before, the spacefaring elves and Jurassic Parked humans were established during character creation). What follows is a truncated series of events, cramming events from multiple sessions, in which the players collectively decide to become landlubbers.

The hospital became its own pre-adventure to what was intended to be a pre-adventure. They didn’t step foot into the Canal of Horrors proper until the 2nd session. I ran the hospital as an improvised dungeon crawl (on a ward-by-ward basis rather than room-by-room. I mapped it to stay just ahead of the party at any given time). They played the hospital like a slapstick comedy. Nowhere was the vaudevillian nature more apparent than in the children’s ward of the hospital. I decided that, in Bastion, children so seldom become ill that the ward was entirely bereft of patients. Instead, it was full of clowns, hoping to one day see a sick child if only so that they may practice the clowning arts upon them. They cleared the ward by telling the clowns that there was a sick child in the lobby (as the dice would have it, this turned out to be true, but more on that later). But their attempt was only partially successful—one clown remained. The toughest, gruffest clown. I played the clown with my best pack-a-day-smoker’s rasp, describing the clown as chewing and puffing on a balloon-animal balloon like one might chew a cigar. They learned this clown, now ancient, was once a sick bairn in this very ward and was themselves saved by a clown. They were now obligated, by the strict code of honor that governs the lives of clowns: to make a sick child laugh. They were not about to shirk their duty. However, one of the player-characters was a pie smuggler with a skill of “slithering.” The pie smuggler slithered behind the clown as the other characters chatted the ear off of the clown. The pie smuggler did not reveal what they carried in their pie earlier, waiting for the appropriately dramatic moment. Such a moment having appeared, they pulled the mackerel from their pie and gave the clown a healthy smack. The clown was dumbstruck but impressed. Then and there, the pie smuggler was inducted into the society of clowns, and given whip cream pies, a water-squiring boutonnière, and other essential equipment. The clown cautioned the pie smuggler, however, that they had big shoes to fill. [pause for laughter] When they got to the lobby much later, the lobby was filled with clowns swarming a terribly-ill youngster and more clowns were arriving by the tiny-car-load. When they pushed their way through the clowns, they learned that the young child had not cracked even a smile at all of the professional-grade buffoonery being brought to bear. “Please sirs,” the child said, “I need medical attention.”

This paragraph is my attempt to yada yada through the intermediate portions of my players’ misadventures. They cured (and caused) a plague. They started a fight with a gang of roughnecked mock-pigeons. They got hired and fired by a mock-cat in a bodega. They befriended a chain-smoking camel. They watched a beautiful sunset on a bridge overlooking the city. They obtained and discarded a palanquin. They intimidated the owner of a food truck into providing them food and lodging. (I decided the food truck would serve some type of fusion food, so I asked two players to write a type of cuisine down and reveal their choices simultaneously and I would combine them. One picked “Indian Food” and the other wrote “Fast Casual.” Thus the food truck became “Curry in a Hurry”). But all of this was in service of arriving at the docks to board the garbage barge. But everything changed when they got a taste—not of curry—but of authority.

Player characters function best as contemptible creatures living at the edges of society. Only such a person could be driven into the waiting arms of the garbage barge, in search of great and minor fortunes. The final in my series of mistakes was to upset this applecart by giving the characters what all players desire but must never obtain: authority. They came across a private police recruiter, who informed them that, due to budget shortfalls, the police force had been privatized. The recruiter was a contractor for such police privatization efforts and wanted to hire them as subcontractors. However, this wasn’t a job. In fact, the party had to pay a fee for the privilege of becoming subcontracted private cops. But, after some debate, they did so. However, they learned that their badges all had expiration dates. They had but 10 days to wield the state-sanctioned monopoly on violence! As one player put it, what do you do when given a wish? You wish for more wishes. And thus, their accumulation of power made them long only to gain more power and for longer. It is not clear whether this quest will take them to the garbage barge, but it will continue to wait for them at the docks, biding its time until it is their only refuge from the compounding mistakes they will undoubtedly make. But if you want to run GarBarge (or any adventure really), it is probably a good idea to actually start at the start instead of appending an extraneous pre-adventure adventure to it.

Unrelated Post-Script

My play-reports tend to get less eyeballs than other blogposts, so I trust that only the most dedicated readers are gazing upon this sentence. I just wanted to let you know that I apologize for the dearth of posts here the last month—real life work has been intruding further and further onto my previous time dedicated to thinking about, writing and playing games. However, hark!, I bring good news: Big Rock Candy Hexcrawl, my pay-what-you-want adventure inspired by leftist folk music, will be out very soon, likely next week! I will do a design commentary on it maybe a week after it comes out, but if you want to keep abreast of that and whatever else stray thoughts worm their way into my head but which are not long enough for a full blogpost, you can follow me on twitter @PrismaticWastes. But even if you avoid the dreaded birdapp, you will hear about it here eventually. I hope that you are excited for Big Rock Candy Hexcrawl, because I am excited for other people to see it!

July 12 Update

Big Rock Candy Hexcrawl is out now! I hope you enjoy it!