What Even Is a “Procedure”?

Dare I start with the worn-out canard of bloggers and claim that this is going to be a short post? Well, I hope it will be, but either way it will have two parts: (Step 1) What is this “procedure” thing you might have heard if you travel in some TTRPG circles? and (Step 2) What is the history of proceduralism? “Procedure” is definitely a popular buzzword tossed around in some design circles (particularly among some of those designers emerging from the wreckage of the OSR movement), but it is more than just a flashy tagline. It is a core but often invisible structure that nearly all games have in one form or another. Procedures are often taken for granted, but giving them their due attention is useful for veteran players and referees and downright enlightening for beginners.

Step 1: What is “Procedure”?

Words are slippery creatures and exceedingly hard to nail down because they keep moving. Nonetheless, some struggle quixotically to cram eternal meaning in the little bits and bobs of language dancing all around us. All graduating high school valedictorians know that Webster’s Dictionary defines “procedure” as “1a: a particular way of accomplishing something or of acting, b: a step in a procedure, 2a: a series of steps followed in a regular definite order, b: a set of instructions for a computer that has a name by which it can be called into action, 3a: a traditional or established way of doing things.” In the specific context of tabletop roleplaying games, a few valiant bloggers have appended their own definitions to procedure. For example, Brendan of Necropraxis described it originally as “the degree to which a game directs your actions as a player or referee”; Ava of Permanent Cranial Damage advised that procedures “provide a framework to structure the game”; Marcia of Traverse Fantasy called it “the ways in which [the conversation between the referee and players] is structured”; the Valinard blog calls the rose of procedure by the name “structural mechanics”; and Gus of All Dead Generations recently distinguished procedure from other mechanics as “a form of rules for outside of play itself, the rules for using the rules”. All of these definitions are not exactly coterminous, but a general shape begins to emerge when viewed broadly.

Procedures are a type of rule that provides the order of operation (which order typically repeats) for a game and works to structure play. That is my synthesized, authoritative and final (for now) definition of a “procedure” in the context of TTRPGs. And I broadly agree with the above-cited sources that rules can generally be divided into two categories: procedural rules (i.e., procedure) and substantive rules (what Gus calls “mechanics”, but I do not think that mechanics, as a term, has such a connotation). While not perfect, here is a good test for whether something is a procedural rule: if you say “And rinse and repeat!” after the description of the procedure, is that statement often true when the procedure is being used? This is why procedures so often take the form of turns, which repeat until the activity has concluded.

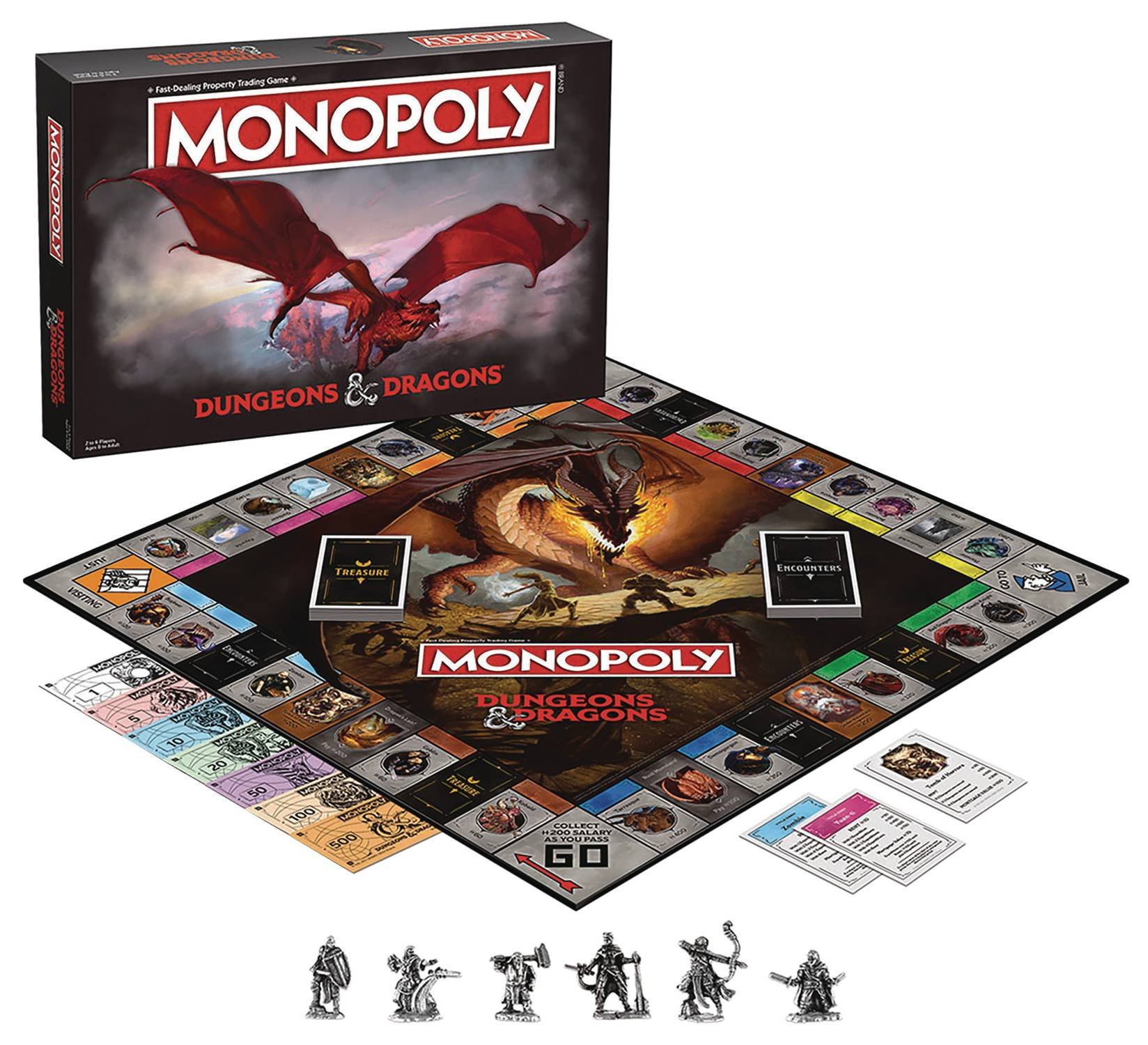

That may all be good and well, but how can one tell the difference between a procedural rule and a substantive rule? To the extent that examples are elucidating, I will give examples of both types of rules in two very different (well, somewhat different) games that I’d imagine most of you are familiar with: Monopoly and Dungeons & Dragons. You likely already know most of these games’ rules well, but categorizing them will help you start to see the procedure (which is often unwritten) in the other games you read, write and play.

Monopoly is a very boring game that simulates how terribly monotonous and unfun capitalism can be. It is also probably one of the most popular board games of all time; closer in stature to chess than to D&D. But this torturous game is also chock-full of procedures! Of primary importance is the basic procedure of monopoly, which structures the rest of the game:

“Starting with the Banker, each player in turn throws the dice. The player with the highest total starts the play: Place your token on the corner marked ‘GO,’ throw the dice and move your token in the direction of the arrow the number of spaces indicated by the dice. After you have completed your play, the turn passes to the left. The tokens remain on the spaces occupied and proceed from that point on the player’s next turn. … According to the space your token reaches, you may be entitled to buy real estate or other properties — or obliged to pay rent, pay taxes, draw a Chance or Community Chest card, ‘Go to Jail®,’ etc.”

This basic procedural rule provides an order of operations for each turn and is repeated until play is done. But many of Monopoly’s rules, such as the rules immediately after Monopoly’s basic procedure (reproduced below), are substantive. These rules don’t structure play or provide an order in which things happen. Instead, these govern specific situations. When that situation happens, you simply do whatever the rule says. If you roll doubles thrice, go to fucking jail! (This could be viewed as a procedure in that it has a temporal aspect of “when X happens, do Y,” but that lacks the structure or repetition to be a proper procedure).

“If you throw doubles, you move your token as usual, the sum of the two dice, and are subject to any privileges or penalties pertaining to the space on which you land. Retaining the dice, throw again and move your token as before. If you throw doubles three times in succession, move your token immediately to the space marked ‘In Jail’.”

Dungeons & Dragons is often derided as being a game with lots of mechanical support for combat but little else. But what is that support other than combat being the main activity in modern D&D that has the benefit of major procedural scaffolding? Simply adding more rules to exploration, like pages and pages of walking speeds for mounts or types of terrain and how that impacts travel, would not add mechanical support to that activity. But adding a procedure, like a hex crawl procedure or an overloaded encounter die for overland travel, gives exploration the structure it needs to stand on its own. So what is the procedural rule that gives D&D combat its oomph?

The most recent edition hides the classic D&D combat procedure deep in the middle of the player’s handbook, but it is there, the classic formula being largely unchanged since the dawn of time in 1974 AD. This combat procedure is the Christmas tree upon which we hang the ornaments that are all the various substantive rules of combat (e.g., how much damage a sword deals, under what conditions the rogue can sneak attack, or how fast a catfolk monk can run in a turn). The procedure outlined below is the little engine that pulls along all that comprises D&D’s combat:

“The game organizes the chaos of combat into a cycle of rounds and turns. ... During a round, each participant in a battle takes a turn. The order of turns is determined at the beginning of a combat encounter, when everyone rolls initiative. Once everyone has taken a turn, the fight continues to the next round if neither side has defeated the other.”

This not only passes the aforementioned “rinse and repeat test,” it basically includes it in the description (with the helpful caveat to stop rinsing and repeating once everyone on one side is dead). And again, we can look right below the procedure to see a set of substantive rules governing how to adjudicate a specific situation in the context of the procedural framework. These rules all govern the same situation (though separate sub-situations, littler edge cases) but do not together form a procedure. Instead, it’s just a miserable little pile of rules. To distinguish the several rules, I have added numerals which are not present in the original text:

“[1] The DM determines who might be surprised. [2a] If neither side tries to be stealthy, they automatically notice each other. [2b] Otherwise, the DM compares the Dexterity (Stealth) checks of anyone hiding with the passive Wisdom (Perception) score of each creature on the opposing side. [3] Any character or monster that doesn’t notice a threat is surprised at the start of the encounter. [4] If you’re surprised, [a] you can’t move or take an action on your first turn in combat, and [b] you can’t take a reaction until that turn ends. [5] A member of a group can be surprised even if the other members aren’t.”

Step 2: What is the History of Proceduralism in TTRPGs?

[The following history originally appeared, in a much less expanded form, in my earlier post on adding procedure to tavern adventures]

Proceduralism, as a descriptive term, has its origin in a 2014 blogpost on Necropraxis. In that post, Brendan analyzed the extent to which proceduralism exists in old-school games and post-Forge story games, such as Torchbearer. Brendan continued on his proceduralist quest in developing the Hazard System (perhaps better known as the overloaded encounter die). Other bloggers during this time were also getting more interested in procedures, whether it was riffing on consensus, writing about haven turns (turns for adventuring in town) or thinking about how various procedures work together in games.

In the post-OSR era, “procedure” made its way to zeitgeist as a result of the Errant RPG crowdfunding campaign by Ava Islam. Ava marketed her system as “rules-light, procedure-heavy”, a formulation that has been remixed by many other games since Errant’s 2021 campaign (it even inspired this “RPG Buzz-Phrase Generator”!). For Errant, these procedures are heavily influenced by the aforementioned Hazard System. A friend of mine and Ava’s, in response to my explanation that procedures are themselves a type of rule posed the question, “If procedures are a type of rule how can a game be rules light procedure heavy?” My response is that the “rules light" designation doesn't really mean the number of rules so much as the cognitive load imposed by using the rules. You could have a game with a single rule but that rule requires you to consult 5 charts and do trigonometry, is that really rules light? Procedures reduce the overhead of running games by providing a framework for play and layering the substantive rules atop that procedural scaffolding. As this blog post from A Knight at the Opera argues, not all rules are equally burdensome, and I would argue that procedures tend toward being the most load-bearing, cognitively speaking, of them all.

Errant’s focus on procedures as a central selling point also caused a resurgence on evaluating procedures in TTRPGS. Many efforts have been made by a small cohort of designers to elevate and expand on the theories laid out by Brendan and popularized by Ava. For instance, my attempt to uncover the basic procedure that unites both OSR games and story games or Gus L’s recent manifesto on the subject. John of the Retired Adventurer blog had this to say on the “The state of Post-OSR content” topic at the tenfootpole forums:

“I think we're actually about to go through a big revival of classic style play, but now attached to new rulesets and more strongly formalised than it was during Gygax[‘s time]. I don't think it's a new play culture such that I would call it "neo-classical" but it's an interesting third wave (after the original and then the early 2000s revival). The key words to look for are a phrase Ava Islam coined to describe her Errant game, which is "rules-light, procedure heavy". This is linked to an emerging "proceduralism" movement (both Marcia, whose Chiquitafajita blog is linked above, and Gus L. of All Dead Generations are advocates, tho' there are many other people as well) is very interested in both studying past classic play and innovating on its techniques and ideas. This movement is still fairly small, and most of its theoretical work is discussed in semi-private fora rather than publicly, but it's starting to recruit and inspire a number of people who might otherwise firmly think of themselves as working with an OSR / post-OSR design tradition.”

Proceduralism is an important trend to keep your eyes on, but one needs not be a proceduralist to benefit from recognizing procedures. Whatever your favorite game, whether it’s Monopoly or Root, D&D or Wanderhome, all games have procedural rules existing alongside their substantive rules. Once you know what to look for (which, if you’ve read this far, you do), you start seeing procedures everywhere. You are probably going through some procedure yourself right now. Rinse and repeat.

Totally unrelated, but I put out a review of an old 5th Edition D&D adventure, from a Post-OSR perspective, on the Bones of Contention blog. I identify some common pitfalls that plague modern D&D adventures and provide some constructive guidance for avoiding those. If you enjoy TTRPG reviews from some of the leading voices of the P/OSR blogosphere, you should check out that blog generally!